Shearwater Research

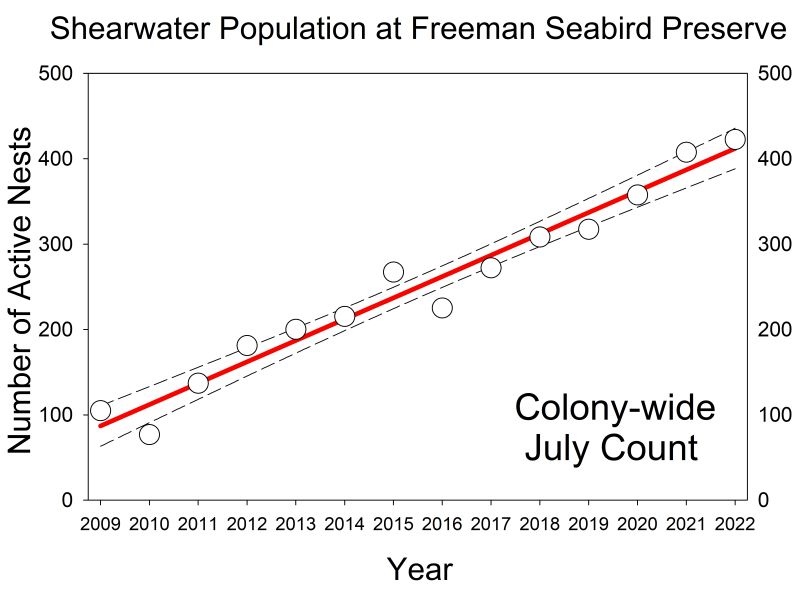

Despite major losses in nesting habitat throughout Hawaiʻi, Wedge-tailed Shearwaters (ʻUaʻu kani) are increasing following conservation efforts to control introduced predators and to restore native vegetation at breeding sites. At the Freeman Seabird Preserve, the collaborative research program that began in 2009 has documented that this unique urban colony has quadrupled in size, from less than 200 breeding birds to over 800 breeding birds (Hyrenbach & Hester 2022).

Caption: Yearly colony census during the peak chick incubation period show a long-term increase in the number of nests at the Freeman Seabird Preserve. On average, the colony grows by 24.9 nests (+/- 5.3 S.D.) each year.

Since 2009, researchers studying the shearwaters at the Freeman Seabird Preserve have learned about their lives at the colony and in the ocean. Explore what we have learned in the tabs below.

Seabirds must return to land to raise their chicks and ʻUaʻu kani parents at FSP look for safe places in rock crevices and artificial clay shelters to raise their single chick. Some of the questions we ask involve: “how many birds return to breed”, “how long are the eggs incubated by the parents”, “do the dates when chicks hatch vary from year to year”, “how well are chicks growing each year”, and “do the artificial nests provide safe nest sites”?

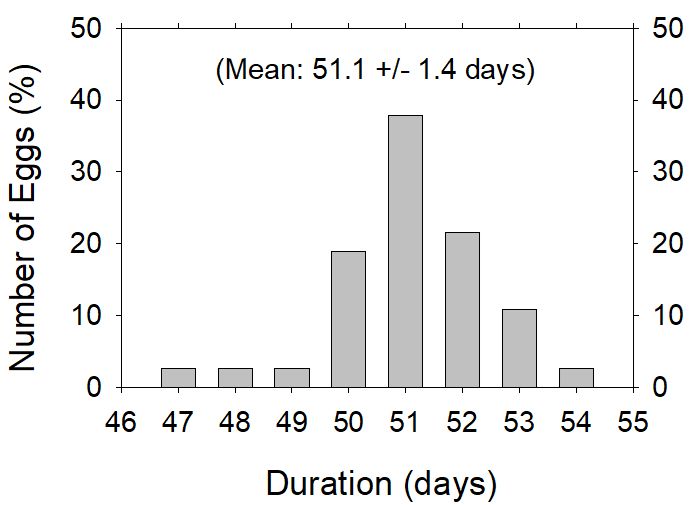

Starting in early June, the shearwater lay and incubate a single egg, which start hatching in late July. By the end of August, all the chicks have hatched. The parents feed their chicks until they fledge, starting in the middle of November.

Caption: Distribution of incubation durations for 37 nests monitored daily revealed a mean incubation of 51.1 ± 1.4 S.D. days (median = 51, range = 47 – 54).

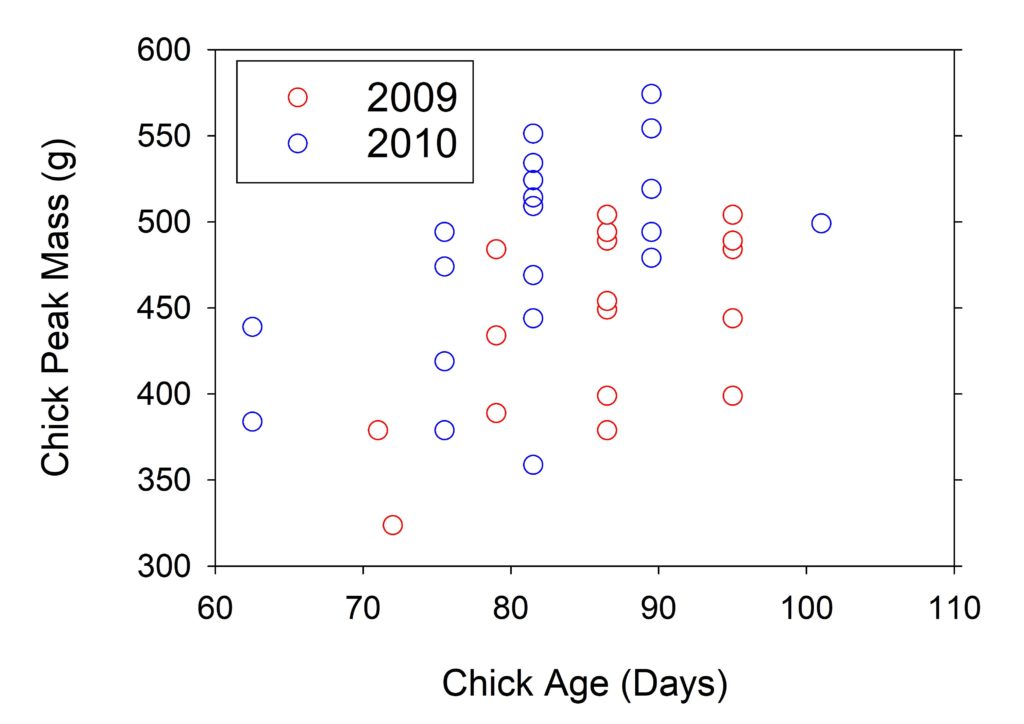

The hatching date influences the growth patterns of the chicks, with the chicks that hatch earlier in the year attaining a larger body mass. Chicks reach their maximum (peak) body mass in late October, when they are 80 – 90 days old. The mass of the chicks starts declining in early November, their parents stop delivering food to the nest. This period of fasting and weight loss stimulates the chicks to leave the nest.

Nevertheless, these dates also vary from year to year, depending on the food conditions at sea. In a “cold-water” year (like 2010), chicks attain a larger peak mass (median weight = 495 grams) sometime in late October (median age = 81.5 days). In a “warm-water” year (like 2009), chicks attain a lower peak mass (median weight = 452.5 grams) about one week later (median age = 86.5 days).

Learn about the shearwater breeding cycle, and ocean conditions influence their breeding success:

https://www.pelagicos.net/Reprints/2015/Pravder_et_al._2015.pdf

https://www.pelagicos.net/pdfs/el0411.pdf

Shearwaters depend on the ocean for food and learning where they feed helps us understand the threats they face. Some of the questions we ask involve: “what do shearwaters eat”, “how far do they travel from the colony”, ‘how deep do they dive”?

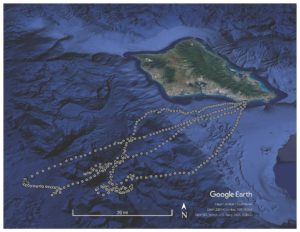

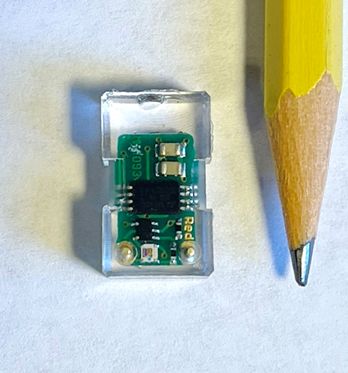

Researchers use a variety of electronic tags to shearwaters to measure their diving, using time-depth recorders, and their movements, using Geographic Positioning System (GPS) and Geolocator (GLS) tags. These tiny devices, which weigh less than 5% of the body mass of the birds, are attached to their feathers with tape or zip-tied to a metal band on their leg.

Caption: Researchers have attached larger GPS tags and smaller TDR tags to study their behavior at-sea.

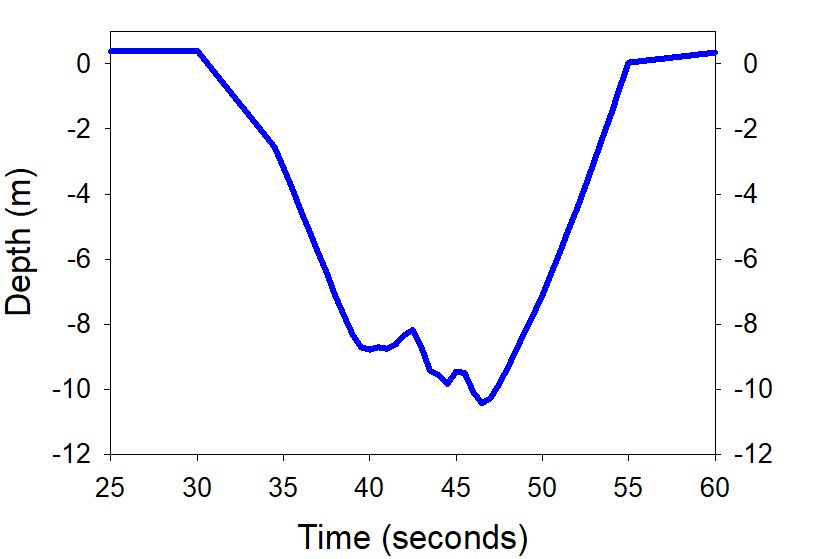

While all tagged shearwaters dove deeper than 1.5 m depth (5 feet), their dives are shallow (mean depth = 6.2 meters) and short (mean duration = 15 seconds). The maximum depth recorded was 21.8 meters (72.7 feet)!

Caption: Example of a 25-second shearwater dive to 10.5 m. The wiggles in the middle of the dive (between the 40 and 47 seconds) suggest this bird was pursuing prey underwater.

Caption: Example of a two foraging trips by a shearwater provisioning a chick at the Freeman Seabird Preserve. This bird repeatedly commuted to an area approximately 60 – 80 miles from the colony, where the contorted paths suggest the shearwater was searching for prey.

Learn more about the shearwater diving behavior:

https://www.pelagicos.net/Reprints/2014/Hyrenbach_et_al._2014_Elepaio_74_1.pdf , (Hyrenbach et al. 2013)

Read about other shearwater tracking and diving studies with our partners from U.S.G.S.:

Adams, J, Felis, JJ, Czapanskiy, MF. 2020. Habitat Affinities and At-Sea Ranging Behaviors among Main Hawaiian Island Seabirds: Breeding Seabird Telemetry, 2013–2016. Camarillo (CA): U.S. Department of the Interior, Bureau of Ocean Energy Management, Pacific OCS Region. OCS Study BOEM 2020-006. 111 pages. https://espis.boem.gov/final%20reports/BOEM_2020-006.pdf

Mystery – Where do shearwaters travel in the winter when they leave Hawaiʻi?

Caption: GLS tags weighting 1.5 grams will be attached to a metal band and deployed on the leg of the shearwaters in August. These tags will record the movements of the shearwaters during the breeding season (August – November) and their winter migration (November – May).

In 2022, HAS is supporting a study to learn where shearwaters go when they leave the colony for the winter. This remains a mystery. Very small GLS sensors attached to bands on their legs will collect light and time data that provides a bird’s location twice a day for over a year (200 – 400 mile accuracy). We will learn where these birds spend their winter holidays and what threats they face in those overwintering grounds, such as overlap with purse-seine fisheries for skipjack tuna.

Resources about these amazing seabirds and ongoing research at FSP:

Light Pollution Threats

https://www.pelagicos.net/research_lightpollution.htm

Entanglement Threats

Seabird Entanglement in Marine Debris and Fishing Gear in the Main Hawaiian Islands (2012 – 2020) (Hyrenbach et al. 2020)

Customized Ceramic Nests

https://www.oikonos.org/initiatives/innovative-nests

Student Research (High School)

Shearwater Nesting on the Black Point Public Right of Way, (Helen Shanefield)

Partners:

Hawaiʻi Pacific University, contact Dr. David Hyrenbach and students (khyrenbach@hpu.edu)

Oikonos – Ecosystem Knowledge

California College of the Arts

Windward Community College

High School and College Students

Community Volunteers

Grants:

U.S.G.S.

Atherton Family Foundation

Disney Conservation Fund